I've decided to move to tumblr! Here is the url:

surilisheth.tumblr.com

Love all, Serve all

Friday, March 25, 2011

Sunday, December 5, 2010

Disillusionment

(Escher)

Futility.

It's a feeling I've heard about from a lot of people recently--a professor telling me why he gave up on the field of development, a friend who went to India and lived in a village for awhile, a friend who can't find a job after graduation, interview panels questioning me about how much of a difference research really makes at the grassroots level, if researching development in India is really "fighting the fight of the world"...

It's something that I felt very strongly the first summer I worked in a slum. It was hard to be happy or to see anything positive when poverty was so entrenched all around me. People had so many issues. Issues that were overlapping with one another, affecting one another, touching everyone in the community, in the city, in the state, in the country, in the world. Intergenerational, cyclical issues that were just piling on top of one another. People were poor, sick, and uneducated. Their parents were poor, sick, and uneducated, and their parents' parents had been poor, sick, and uneducated, too. Where could anyone, let alone me, possibly start? If this one slum area, with 150,000 residents, was making me feel like this, how in the world could I possibly address the fact that India has the most poor people in the world? According to a recent estimate, the nation has over 421 million in just its 8 poorest states (Multidimensional Poverty Index developed at Oxford, based on Amartya Sen's human capabilities approach). The largest number of poor people in the world.

(Escher)

I came back after that summer unable to spend any money except for the bare essentials for months. I felt guilty and unsure of what I could possibly do in this world so full of inequality and poverty. This was important for me to go through, because I didn't realize it at the time, but it caused my mind to keep trying out new ideas, to keep searching for the beginnings of solutions. I couldn't see any other alternative. I came back to my university and took some classes. I read about the experiments being conducted by the MIT Poverty Action Lab. I went back to India and opened my eyes, focusing not only on the suffering but also on the inspirational people that were all around me--NGO workers, children from the slum who were studying hard so they could bring their families out of a cycle of poverty. Men and women and children who were working to rid their world of injustice.

No one who found any of the amazing solutions to problems in the world ever did so because they gave up. And who am I to give up when there are people out there literally fighting for their lives and for the lives of their families? Who have been fighting for generations to survive and to have a voice? Parents are struggling to put food in front of their children every day, children are struggling to balance surviving with studying, and I'm the one giving up? How does that makes sense?

Speaking specifically about the field of development, perhaps it's one of the easiest fields to get disillusioned with. And don't get me wrong--realizing the magnitude of the problems there are is extremely important. Grasping their complexity is significant, and we must pick out the problems in our respective fields so we can reform them. So we can keep changing the system, making it as dynamic as the world is. These concepts of balancing idealism with pragmatism, targeting researching to the grassroots, merging theory and reality, are ones that I'm struggling with, and they're concepts that I hope I keep struggling with. Because the difference is in the struggle.

Here is the wonderful thing: helping a single child to study could lead to an escape for her (if not her family's) cycle of poverty. And that, in itself, is most definitely "enough." If I do that, I am one human being, and I have made a difference to one entire other human being (and that's discounting any positive externalities). That's not a small success. It's huge. And it's the place that I had a chance to start addressing all of the bad I saw around me.

Little events, ordinary things, smashed and reconstituted. Imbued with new meaning. Suddenly they become the bleached bones of a story.

-The God of Small Things

Keeping on trying is the next step. I owe it to myself and as a person who lives in a world full of other people. Giving up is not going to accomplish anything, but it is going to take away one mind and one heart from the fight that makes the world better. Addressing that fight through whatever corner you choose to address it from, I think is most definitely "fighting the fight of the world." Everything that each one of us does is connected to everyone else. I believe that we are each responsible for realizing this, and this realization alone should stop us from giving up

"Cass Mastern lived for a few years and in that time he learned that the world is all of one piece. He learned that the world is like an enormous spider web and if you touch it, however lightly, at any point, the vibration ripples to the remotest perimeter and the drowsy spider feels the tingle and is drowsy no more but springs out to fling the gossamer coils about you who have touched the web and then inject the black, numbing poison under your hide." -All the King's Men

So, this is my plea. Face and learn from the problems you see everywhere, but don't ever give up. Disillusionment happens, and perhaps everyone faces it at some point in their lives. But I think it's a motivation, not a reason to give up. Allow others to question you, your motivations, your goals, and your work. Let your experiences make you reevaluate what you're doing. Keep changing. But don't let anything make you walk away from the work or the people you love. Have faith in yourself and in those around you. We're the ones that get to make a difference today, tomorrow, and for the rest of our lives--through research, through medicine, through media...pick the avenue you love and go for it. Change paths if you like--once, twice, three times--but don't ever stop. Constant reevaluation, perseverance, connection, and love are how we go about changing an unjust system. I have to remind myself of that at times, but it always ends up coming back. It's my mantra and I plan to stick by it.

(Escher)

"A man goes out on a beach and sees that it is covered with starfish that have washed up in the tide. A little boy is walking along, picking them up and throwing them back into the water. "What are you doing, son?" the man asks. "You see how many starfish there are? You'll never make a difference." The boy paused thoughtfully, and picked up another starfish and threw it into the ocean. "It sure made a difference to that one," he said."

-Hawaiian parable

Wednesday, November 24, 2010

Saturday, September 18, 2010

The Intellectual

While reading the Oxford MPhil in Development Studies Handbook, I came across the wonderful excerpt and wanted to share:

"The central fact for me is, I think, that the intellectual is an individual endowed with a faculty for representing, embodying, articulating a message, a view, an attitude, philosophy or opinion to, as well as for, a public. And this role has an edge to it, and cannot be played without a sense of being someone whose place it is publicly to raise embarrassing questions, to confront orthodoxy and dogma (rather than to produce them), to be someone who cannot easily be co-opted by governments and corporations, and whose raison d'etre is to represent all those people and issues that are routinely forgotten or swept under the rug. The intellectual does so on the basis of universal principles: that all human beings are entitled to expect decent standards of behaviour concerning freedom and justice from worldly power or nations, and that deliberate or inadvertent violations of these standards need to be testified and fought against courageously."

Edward Said, Reith Lectures, June 1993

Personally, I think that these are the responsibilities of everyone--whether they fancy themselves intellectuals or not.

On a separate note, I came back from my trip with dad to Ireland and England. Oxford's campus was truly gorgeous and made me want to spend much more time than I had with the beauty, history, and art that surrounded me. Trinity College's campus was not as aesthetically pleasing, but the tour given by an eighth year history student (haha, yes, 8) and his retelling of amusing/slightly horrific stories about the professors, students, (e.g. students threw bricks in the windows of a young and apparently widely unpopular college professor (the professors then stayed in the buildings on the campus, which we were standing in front of when this story was told). In turn, the professor decided to bring out his gun and start shooting at them. So of course, the students returned with their own guns...in the end, the professor was very unfortunately fatally wounded in an area where a man really would not want to be wounded. The judge dismissed the students from all charges {which of course had nothing to do with the fact that their fathers were in high places, said our guide sarcastically). They went on to hold high places in Irish government and academia themselves, apparently.) and architecture of the college made it quite an interesting place to visit.

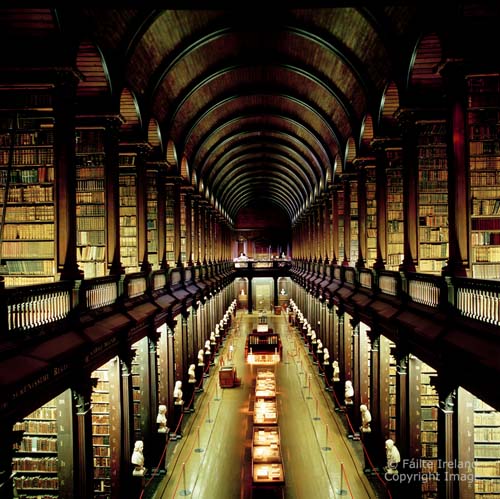

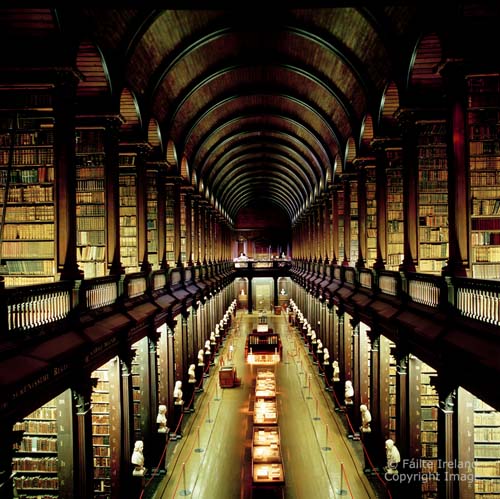

And then there was the Old Library at Trinity College. I wanted to sit there for weeks just to admire the wood and ladders and leather books. There was an exhibition called "Nabobs, Soldiers and Imperial Service: The Irish in India" which displayed many books written by British and Irish with unique perspectives on their relationships with India.

In London, I was able to meet up with some British friends I had made at Manav Sadhna, and the Irish really are the friendliest people on the planet. The greenery in Ireland was breathtaking, and Galway was probably my favorite city. On our first night in Galway, we went to dinner with my dad's colleagues and hosts--an Austrian professor, a German professor, and a French postdoc. Needless to say, the three-hour dinner quite entertaining, with topics of conversation ranging from information technology to healthcare to slums to Chinese infrastructure to, of course, which country is better--Germany or Austria (a topic discussed more and more animatedly by aforementioned professors as the night wore on!).

A 10 day trip was certainly not nearly long enough but alas, I must start classes for my last year at Ohio State after almost nine months away...

"The central fact for me is, I think, that the intellectual is an individual endowed with a faculty for representing, embodying, articulating a message, a view, an attitude, philosophy or opinion to, as well as for, a public. And this role has an edge to it, and cannot be played without a sense of being someone whose place it is publicly to raise embarrassing questions, to confront orthodoxy and dogma (rather than to produce them), to be someone who cannot easily be co-opted by governments and corporations, and whose raison d'etre is to represent all those people and issues that are routinely forgotten or swept under the rug. The intellectual does so on the basis of universal principles: that all human beings are entitled to expect decent standards of behaviour concerning freedom and justice from worldly power or nations, and that deliberate or inadvertent violations of these standards need to be testified and fought against courageously."

Edward Said, Reith Lectures, June 1993

Personally, I think that these are the responsibilities of everyone--whether they fancy themselves intellectuals or not.

On a separate note, I came back from my trip with dad to Ireland and England. Oxford's campus was truly gorgeous and made me want to spend much more time than I had with the beauty, history, and art that surrounded me. Trinity College's campus was not as aesthetically pleasing, but the tour given by an eighth year history student (haha, yes, 8) and his retelling of amusing/slightly horrific stories about the professors, students, (e.g. students threw bricks in the windows of a young and apparently widely unpopular college professor (the professors then stayed in the buildings on the campus, which we were standing in front of when this story was told). In turn, the professor decided to bring out his gun and start shooting at them. So of course, the students returned with their own guns...in the end, the professor was very unfortunately fatally wounded in an area where a man really would not want to be wounded. The judge dismissed the students from all charges {which of course had nothing to do with the fact that their fathers were in high places, said our guide sarcastically). They went on to hold high places in Irish government and academia themselves, apparently.) and architecture of the college made it quite an interesting place to visit.

And then there was the Old Library at Trinity College. I wanted to sit there for weeks just to admire the wood and ladders and leather books. There was an exhibition called "Nabobs, Soldiers and Imperial Service: The Irish in India" which displayed many books written by British and Irish with unique perspectives on their relationships with India.

In London, I was able to meet up with some British friends I had made at Manav Sadhna, and the Irish really are the friendliest people on the planet. The greenery in Ireland was breathtaking, and Galway was probably my favorite city. On our first night in Galway, we went to dinner with my dad's colleagues and hosts--an Austrian professor, a German professor, and a French postdoc. Needless to say, the three-hour dinner quite entertaining, with topics of conversation ranging from information technology to healthcare to slums to Chinese infrastructure to, of course, which country is better--Germany or Austria (a topic discussed more and more animatedly by aforementioned professors as the night wore on!).

A 10 day trip was certainly not nearly long enough but alas, I must start classes for my last year at Ohio State after almost nine months away...

Tuesday, August 3, 2010

Deepak: An Update

I should have actually written this update when I was still in Ahmedabad, but somehow, time, as always, escaped me.

I ended up spending more and more time with Deepak and his mother, going by his home in the Tekro often with Sunilbhai or Ajaybhai to talk to his mom about taking him to the municipal hospital just to get a checkup. Finally, we agreed on a date. However, on that same day, Sunilbhai had to go somewhere else; I did not want all of the effort of finally convincing Deepak's mother to go to the hospital to go to waste, so I still went by their home and sure enough, they were ready to go. I was determined we would go. With a few phone calls, I got Ramanbhai, another very dedicated Manav Sadhna staff member who has a badge to let us into the municipal hospital, to come and help take Deepak and his mother there. We spent about 6 hours at the municipal hospital, where Deepak had a 2 minute check-up and echocardiogram taken.

The doctor explained to us how there was a hole between the bottom two chambers of Deepak's heart--so, blood that was not completely clean was being pumped through his entire body, thus stunting his growth, causing his shortness of breath, and various other problems. An 8 hour operation that would place a pipe near his heart would help solve this problem. Though his SPO2 level was measured at 70%, which is extremely low, the doctor, after hearing about Deepak's parents' reluctance to have an operation done, told them to just bring him in every 3 months for a checkup and to keep monitoring if his symptoms worsened (dizziness, etc.).

Spending 6 hours in line at the hospital with Ramanbhai, Deepak, and his mother turned out to be a blessing in disguise. I spent much of the time talking to Deepak's mother, getting to know her, finding out what her reservations about Deepak's possible operation were, and building a relationship with her. She told me about how she had seen neighbors in the Tekro slum around her get very sick, go to the hospital, and never come back. She didn't want that to happen to Deepak, and an 8 hour operation sounded very long and scary for her little boy. The only symptom Deepak shows, she kept repeating to me, is a shortness of breath--nothing as extreme as she's seen with other sick people in the slum, so Deepak can't be that bad off, right? I explained to her what the doctor said about Deepak's heart, that shortness of breath at the age of 9 is actually quite a worrisome symptom. Very soon, I saw that a difference was made in her mind not by the content of our conversation but rather by the conversation itself--the fact that I was sitting down and talking to her for hours, telling her about myself and letting her tell me about herself and her son. Soon, she was giving me her phone number and asking me questions about Deepak's condition without any prompting.

Speaking with Kirsten, a neonatal nurse back in the US who was volunteering with me at Manav Sadhna (her and her friend Nattie came to India for the first time for a couple of weeks--only one of which was to be spent at Manav Sadhna-- and ended up not traveling to the other places they were going to go and quitting their jobs, staying for 3 months to volunteer with Manav Sadhna), I learned that she was extremely surprised about the doctor's recommendation that Deepak just come in for regular checkups when his SPO2 level was so low. Doing some research myself, I found out that a normal SPO2 level is well above 90%. Talking to Sunilbhai, who has connections with local cardiologists since he has been a health worker for MS for 8 years, we agreed that Deepak should be taken to a private cardiologist, who may be able to spend more time on Deepak's case. I was apprehensive about Deepak's parents' reaction to another trip to the doctor, especially after it had taken so much convincing to go through with the last one. However, when I showed up at Deepak's home with ice cream, markers, and sketchpads and mentioned that I thought he should go to a private cardiologist (and assured his mother it would not take as long as going to the government hospital), his mother was ready to take him--the very first time I told her!

Once again, I found that building a relationship--the simple small acts of taking the time to talk to her, touch her arm, smile at her, show her I care about her son--accomplished much more than just repeating to her that she was not doing enough for her son. Because Deepak's mother trusted me, she was willing to try a new approach to her son's illness--one that she fears but now understands may be a better path to take than the one she has been treading on.

I've been in touch with Sunilbhai since I have been back in the States and hope to hear more about Deepak soon.

I ended up spending more and more time with Deepak and his mother, going by his home in the Tekro often with Sunilbhai or Ajaybhai to talk to his mom about taking him to the municipal hospital just to get a checkup. Finally, we agreed on a date. However, on that same day, Sunilbhai had to go somewhere else; I did not want all of the effort of finally convincing Deepak's mother to go to the hospital to go to waste, so I still went by their home and sure enough, they were ready to go. I was determined we would go. With a few phone calls, I got Ramanbhai, another very dedicated Manav Sadhna staff member who has a badge to let us into the municipal hospital, to come and help take Deepak and his mother there. We spent about 6 hours at the municipal hospital, where Deepak had a 2 minute check-up and echocardiogram taken.

The doctor explained to us how there was a hole between the bottom two chambers of Deepak's heart--so, blood that was not completely clean was being pumped through his entire body, thus stunting his growth, causing his shortness of breath, and various other problems. An 8 hour operation that would place a pipe near his heart would help solve this problem. Though his SPO2 level was measured at 70%, which is extremely low, the doctor, after hearing about Deepak's parents' reluctance to have an operation done, told them to just bring him in every 3 months for a checkup and to keep monitoring if his symptoms worsened (dizziness, etc.).

Spending 6 hours in line at the hospital with Ramanbhai, Deepak, and his mother turned out to be a blessing in disguise. I spent much of the time talking to Deepak's mother, getting to know her, finding out what her reservations about Deepak's possible operation were, and building a relationship with her. She told me about how she had seen neighbors in the Tekro slum around her get very sick, go to the hospital, and never come back. She didn't want that to happen to Deepak, and an 8 hour operation sounded very long and scary for her little boy. The only symptom Deepak shows, she kept repeating to me, is a shortness of breath--nothing as extreme as she's seen with other sick people in the slum, so Deepak can't be that bad off, right? I explained to her what the doctor said about Deepak's heart, that shortness of breath at the age of 9 is actually quite a worrisome symptom. Very soon, I saw that a difference was made in her mind not by the content of our conversation but rather by the conversation itself--the fact that I was sitting down and talking to her for hours, telling her about myself and letting her tell me about herself and her son. Soon, she was giving me her phone number and asking me questions about Deepak's condition without any prompting.

Speaking with Kirsten, a neonatal nurse back in the US who was volunteering with me at Manav Sadhna (her and her friend Nattie came to India for the first time for a couple of weeks--only one of which was to be spent at Manav Sadhna-- and ended up not traveling to the other places they were going to go and quitting their jobs, staying for 3 months to volunteer with Manav Sadhna), I learned that she was extremely surprised about the doctor's recommendation that Deepak just come in for regular checkups when his SPO2 level was so low. Doing some research myself, I found out that a normal SPO2 level is well above 90%. Talking to Sunilbhai, who has connections with local cardiologists since he has been a health worker for MS for 8 years, we agreed that Deepak should be taken to a private cardiologist, who may be able to spend more time on Deepak's case. I was apprehensive about Deepak's parents' reaction to another trip to the doctor, especially after it had taken so much convincing to go through with the last one. However, when I showed up at Deepak's home with ice cream, markers, and sketchpads and mentioned that I thought he should go to a private cardiologist (and assured his mother it would not take as long as going to the government hospital), his mother was ready to take him--the very first time I told her!

Once again, I found that building a relationship--the simple small acts of taking the time to talk to her, touch her arm, smile at her, show her I care about her son--accomplished much more than just repeating to her that she was not doing enough for her son. Because Deepak's mother trusted me, she was willing to try a new approach to her son's illness--one that she fears but now understands may be a better path to take than the one she has been treading on.

I've been in touch with Sunilbhai since I have been back in the States and hope to hear more about Deepak soon.

Monday, July 26, 2010

Mera Kam Khatam! (My Work is Over), Part II

My uncle, cousin and I arrived at the Mumbai FRO around 9am. When we got to the front of the line of foreigners and explained my situation, the woman at the front desk mater-of-factually responded that no one had called about my case, and sorry but paperwork was certainly going to take more than one day. The Mumbai FRO office closes at 1pm, which is when they start their paperwork, and they were going to have to communicate with the Jaipur FRO office via fax; the Jaipur FRO office would have to fax back and besides, there was a bunch of other paperwork that would also have to be processed for me to get my Exit Permit.

This time, I was ready. I had bought 100 Rs. (=100 minutes) on my phone (all of which would be used up by the end of the day) so I could call back and forth to Jaipur. As my uncle and cousin waited in the waiting room, I went inside got my paperwork started to be processed--my uncle wrote a note saying I was living with him in Mumbai and I produced whatever papers I could find that showed I had studied with a registered program in Jaipur. I called my professors/director of the study abroad program in Jaipur and told them about how I needed the Jaipur FRO to respond ASAP to the communication that the Mumbai FRO sent via fax, and one of my professors was headed over to the Jaipur FRO with a folder holding papers about me to present my case. That is when the lady I was working with informed me that it was my responsibility to get the phone and fax number of the Jaipur FRO--of course, it's not like all of the government offices in different states actually have a directory of phone numbers for or methods of communication with each other!

As I kept calling Jaipur to check up on the status of my case being made there, I was informed that I was not allowed to use a cell phone in the FRO waiting room (even though somehow, I was supposed to conjure up the number for the Jaipur FRO myself). So, running in and out of the office every few minutes, an hour later, I found out that my professor had reached the FRO in Jaipur and was explaining my case. I asked him to please tell me the fax and phone numbers for the government office he was in...and he informed me that apparently, there was no land-line phone number, nor was there a fax machine...yes, that is correct, the government Foreign Registration Office of this large and well-known city has no phone number.

Many frantic phone calls later, I finally had a random cell phone number and the number of a fax "nearby" which the Jaipur FRO officer relayed through my professor. By this time it was almost 1pm. A fax was sent from Mumbai to Jaipur asking them to confirm that my exiting the country was O.K. I thought my work was almost done and my paperwork would be processed now. But I breathed a sigh of relief too quickly.

The lady who was processing my paperwork informed me I had yet to fill out an exit permit, which could be done on one of the computers, put passport pictures of myself (which I did not have) on it, write a long letter about why I was in the situation I was in, and do a million other pieces of paperwork, each of which she only told me about when I thought I had turned the last piece of paperwork in. Running in and out of the waiting room (which had now emptied of foreigners since it was after 1pm--only my cousin and uncle remained sitting there) one good thing happened-- through our many interactions the lady who was processing my paperwork had softened a bit toward me and told me that though this was a lot more work for her and she had a lot of other people's paperwork to do, she would process mine if the fax from the Jaipur FRO came back in time--it would have to arrive before 3pm or there was no hope of my paperwork being processed.

My cousin and I ran across the street to a small Kodak shop to get passport photos. When the man handed me my pictures, I asked for my 50 Rs. change back (the pictures had been 50 Rs. and I had handed a man 100 Rs.), to which the man giving me my photos said that the man I had initially given my money to had left for namaz and did not tell anyone that I needed change. By this point, I was quite enraged, but there was nothing I could do--50 Rs. is just a little over $1, but I was determined to not be cheated and vowed I would come back (it was the principle of the matter!). But right now, I had to run back with my photos and make sure my paperwork was processed on time.

We ran back across the street when I got the phone call from my professor, still at the Jaipur FRO, that a fax had been sent back to Mumbai! Jumping for joy, I crowded into the lift and ran into the 3rd floor office once more, where I was informed the fax had reached. I filled out paperwork, signed, pasted photographs, and xeroxed forms for the next hour and finally was informed that all I had to do was pay a $30 fine. Pretty peeved since this was clearly the Jaipur FRO officer's fault, I got a yellow receipt from a lady at the front desk (I wanted to see if I could be reimbursed from my program). However, the lady that had processed my paperwork took that receipt for her records so I went back to the lady who had given me a receipt and asked for the white copy. Setting her jaw and not even bothering to look for my copy, she said she had given me a receipt and she didn't have any other copy--"mera kam khatam" (my work is over), she said, crossing her arms and not budging. No matter what I said nicely (the only other people in the room were my uncle, cousin, and the xerox man who agreed with me that she had not given me the correct receipt), she just kept repeating "mera kam khatam". Having been in the FRO for over 6 hours now, I was more than a little angry and each repetition of the phrase riled me up a little more. In slightly broken Hindi, I proclaimed that I was not leaving without my receipt and started rifling through the papers on her desk myself (my cousin and uncle looked on slightly amused--later on, my cousin told me she was going to come help me with the bullish receipt woman but it seemed I was taking care of myself just fine). I broke through the last barrier of the bureaucracy, as my rifling through her papers finally pushed her into action. Kind of sheepishly (though never admitting any mistake), she found my receipt and I left the office triumphant, 7 hours after I had first entered. I had an exit permit dated for June 7--if for some reason I was unable to leave the country today, well...I didn't want to think about that.

I ran back across the street to the photographer's office and demanded my 50 Rs. Back from namaz and apologizing under what I like to think of as my withering glare, he handed over my money and I rode home reveling in my small victory.

At the airport, my uncle's driver unloaded my luggage from the trunk for the third night in a row. Begging me to please catch the plane this time, I tried to reassure him that I would (really hoping I was right this time). When I walked into the airport, all of the Continental greeted me by name--the ones checking passports, managing the lines, and at the check-in counters. As I pushed my trolley and pulled up my now over-sized jeans, I flashed them wide grins. The nice man who had escorted me around the night before asked if I had my registration as he checked my passport again and, a little loudly, I waved the prized piece of paper that had been stamped, signed, and had my picture on it--my exit permit-- in his face."I CAN LEAVE INDIA NOW!!!" (he looked around a little embarrassedly at my volume, but flashed me a quick smile, congratulated me, and walked away). I sailed through Immigration on a cloud.

Of course, monsoon had just started in Mumbai, I went through a million extra security checkpoints after reaching the gate for some reason, and everyone on my plane sat in a room behind the gate for about 3 hours in the muggy humidity before a man yelled up a storm to the poor airport staff for not having AC in the room (they finally brought two jumbo fans down). When I got on the plane, I learned that because of the rains, they needed to reduce the weight of the plane so about half of the passengers were not flying with us anymore; however, their luggage had already been loaded and needed to be unloaded. After another couple of hours of sitting at the gate, the plane finally lifted off and we were informed the in-flight entertainment system was not going to work. At this point, I really didn't care--I stretched out on 3 empty seats and slept for 14 hours straight. I was finally going home.

This time, I was ready. I had bought 100 Rs. (=100 minutes) on my phone (all of which would be used up by the end of the day) so I could call back and forth to Jaipur. As my uncle and cousin waited in the waiting room, I went inside got my paperwork started to be processed--my uncle wrote a note saying I was living with him in Mumbai and I produced whatever papers I could find that showed I had studied with a registered program in Jaipur. I called my professors/director of the study abroad program in Jaipur and told them about how I needed the Jaipur FRO to respond ASAP to the communication that the Mumbai FRO sent via fax, and one of my professors was headed over to the Jaipur FRO with a folder holding papers about me to present my case. That is when the lady I was working with informed me that it was my responsibility to get the phone and fax number of the Jaipur FRO--of course, it's not like all of the government offices in different states actually have a directory of phone numbers for or methods of communication with each other!

As I kept calling Jaipur to check up on the status of my case being made there, I was informed that I was not allowed to use a cell phone in the FRO waiting room (even though somehow, I was supposed to conjure up the number for the Jaipur FRO myself). So, running in and out of the office every few minutes, an hour later, I found out that my professor had reached the FRO in Jaipur and was explaining my case. I asked him to please tell me the fax and phone numbers for the government office he was in...and he informed me that apparently, there was no land-line phone number, nor was there a fax machine...yes, that is correct, the government Foreign Registration Office of this large and well-known city has no phone number.

Many frantic phone calls later, I finally had a random cell phone number and the number of a fax "nearby" which the Jaipur FRO officer relayed through my professor. By this time it was almost 1pm. A fax was sent from Mumbai to Jaipur asking them to confirm that my exiting the country was O.K. I thought my work was almost done and my paperwork would be processed now. But I breathed a sigh of relief too quickly.

The lady who was processing my paperwork informed me I had yet to fill out an exit permit, which could be done on one of the computers, put passport pictures of myself (which I did not have) on it, write a long letter about why I was in the situation I was in, and do a million other pieces of paperwork, each of which she only told me about when I thought I had turned the last piece of paperwork in. Running in and out of the waiting room (which had now emptied of foreigners since it was after 1pm--only my cousin and uncle remained sitting there) one good thing happened-- through our many interactions the lady who was processing my paperwork had softened a bit toward me and told me that though this was a lot more work for her and she had a lot of other people's paperwork to do, she would process mine if the fax from the Jaipur FRO came back in time--it would have to arrive before 3pm or there was no hope of my paperwork being processed.

My cousin and I ran across the street to a small Kodak shop to get passport photos. When the man handed me my pictures, I asked for my 50 Rs. change back (the pictures had been 50 Rs. and I had handed a man 100 Rs.), to which the man giving me my photos said that the man I had initially given my money to had left for namaz and did not tell anyone that I needed change. By this point, I was quite enraged, but there was nothing I could do--50 Rs. is just a little over $1, but I was determined to not be cheated and vowed I would come back (it was the principle of the matter!). But right now, I had to run back with my photos and make sure my paperwork was processed on time.

We ran back across the street when I got the phone call from my professor, still at the Jaipur FRO, that a fax had been sent back to Mumbai! Jumping for joy, I crowded into the lift and ran into the 3rd floor office once more, where I was informed the fax had reached. I filled out paperwork, signed, pasted photographs, and xeroxed forms for the next hour and finally was informed that all I had to do was pay a $30 fine. Pretty peeved since this was clearly the Jaipur FRO officer's fault, I got a yellow receipt from a lady at the front desk (I wanted to see if I could be reimbursed from my program). However, the lady that had processed my paperwork took that receipt for her records so I went back to the lady who had given me a receipt and asked for the white copy. Setting her jaw and not even bothering to look for my copy, she said she had given me a receipt and she didn't have any other copy--"mera kam khatam" (my work is over), she said, crossing her arms and not budging. No matter what I said nicely (the only other people in the room were my uncle, cousin, and the xerox man who agreed with me that she had not given me the correct receipt), she just kept repeating "mera kam khatam". Having been in the FRO for over 6 hours now, I was more than a little angry and each repetition of the phrase riled me up a little more. In slightly broken Hindi, I proclaimed that I was not leaving without my receipt and started rifling through the papers on her desk myself (my cousin and uncle looked on slightly amused--later on, my cousin told me she was going to come help me with the bullish receipt woman but it seemed I was taking care of myself just fine). I broke through the last barrier of the bureaucracy, as my rifling through her papers finally pushed her into action. Kind of sheepishly (though never admitting any mistake), she found my receipt and I left the office triumphant, 7 hours after I had first entered. I had an exit permit dated for June 7--if for some reason I was unable to leave the country today, well...I didn't want to think about that.

I ran back across the street to the photographer's office and demanded my 50 Rs. Back from namaz and apologizing under what I like to think of as my withering glare, he handed over my money and I rode home reveling in my small victory.

At the airport, my uncle's driver unloaded my luggage from the trunk for the third night in a row. Begging me to please catch the plane this time, I tried to reassure him that I would (really hoping I was right this time). When I walked into the airport, all of the Continental greeted me by name--the ones checking passports, managing the lines, and at the check-in counters. As I pushed my trolley and pulled up my now over-sized jeans, I flashed them wide grins. The nice man who had escorted me around the night before asked if I had my registration as he checked my passport again and, a little loudly, I waved the prized piece of paper that had been stamped, signed, and had my picture on it--my exit permit-- in his face."I CAN LEAVE INDIA NOW!!!" (he looked around a little embarrassedly at my volume, but flashed me a quick smile, congratulated me, and walked away). I sailed through Immigration on a cloud.

Of course, monsoon had just started in Mumbai, I went through a million extra security checkpoints after reaching the gate for some reason, and everyone on my plane sat in a room behind the gate for about 3 hours in the muggy humidity before a man yelled up a storm to the poor airport staff for not having AC in the room (they finally brought two jumbo fans down). When I got on the plane, I learned that because of the rains, they needed to reduce the weight of the plane so about half of the passengers were not flying with us anymore; however, their luggage had already been loaded and needed to be unloaded. After another couple of hours of sitting at the gate, the plane finally lifted off and we were informed the in-flight entertainment system was not going to work. At this point, I really didn't care--I stretched out on 3 empty seats and slept for 14 hours straight. I was finally going home.

Bureaucracy at its finest, Part I

I've been back from India for over a month now, but on June 6, 2010 I really wasn't sure if I was going to make it.

I was dropped off at the Mumbai airport 9pm with all of my luggage for the second night in a row (my dad had accidentally switched my flights the night before, so though the driver had dropped me off, when I got to the check-in desk, I found that my itinerary was for the next day). Of course, when I got to the front of the check-in line, one bag weighed too much and I hurriedly started stuffing things from one bag into another. Finally getting both bags to their correct weight limit, I again went through the line, when a Continental staff member examined my passport and asked to see my registration. "What registration? The Jaipur Foreign Registration Office (FRO) said I didn't need to register since my visa was under 6 months..." The nice Continental guy told me he would put my luggage on hold until Immigration cleared me. That's when my panic started. I had just read all about how Indian Immigration had gotten very strict with American citizens in allowing them to enter and re-enter the country; however, I didn't know they would also stop me from LEAVING! Having had many experiences in getting through bureaucracy to get where I needed when I helped take slum children to the municipal (government) hospital with Manav Sadhna, I put on my polite-but-won't-back-down face and went back to immigration.

As predicted, when I got to the immigration officer, he took one look at my student visa and asked for my registration. I repeated what I had said before--that my study abroad program had taken our whole student group to register at the Jaipur FRO, but they told some of us that we did not need to register and sent us back--and all of the other students in my program were allowed to go back to the US. What could I do if the FRO officer didn't give me registration papers? Of course there is no computer system that records these kinds of things--people who have gone to the FRO and registered, people that haven't, people that have gone and were not given registration--why use technology to lessen paperwork? No, just like medical records and tax records, these sorts of things are all recorded on papers that have to be stamped, signed, and photographed multiple times--papers that we all have to carry around if we have any hope of getting anything done.

[Pictures of the AUDA tax office in Usmapura in Ahmedabad.The room goes on for awhile, and all of the shelves, tables, and most of the floorspace is occupied by dusty files containing tax information. One lone desktop computer sits in the corner of the room--located on the left side of the top picture--and only those lucky enough to have a key number have their business taken care of by using a computerized system. For everyone else, tax officers sit and sort through thousands of names in files which are organized by some archaic system that is not alphabetical and which I have a real suspicion that even the government workers in the office do not know how to search through...we almost went through that process when we were there, but luckily, Ajaybhai called and found a number and we were able to look up the file on the COMPUTER!]

{also, the pictures of Hindu gods in a government office may seem surprising for a democracy, but that has to do with India's definition of secularism, which is quite different from the western definition...but I'll leave that discussion for later!}

I was sent back out to look through my packed luggage to see if my registration papers were hidden somewhere. So, I frantically began searching through my check-in baggage in the middle of the airport, stacking all of the papers I had stuffed in my bag (I am supposed to lug home all of the materials I used in my study abroad classes to make sure I get appropriate credit from my university) all around me as the nice Continental guy stood looking down at me sympathetically. I called my professors in Jaipur telling them what was going on, and they confirmed my fears--I could not find my registration papers because the Jaipur FRO did not give me any. As the nice Continental guy started ripping my check-in tags off my baggage, I held back tears, determined not to look more pitiful than I already did--in the middle of the airport pulling up my jeans that were now a million sizes too big because of all the weight I had lost, disheveled hair in a ponytail that was loosening itself by the minute, with about 10 pounds of paper now strewn across the floor. Gathering everything onto a trolley, I went back to the immigration officer to see if I could talk my way onto the plane.

Of course, I wasn't allowed. He walked me and all of the luggage I was heaving around back to the offices of his supervisor and his supervisor's supervisor and his supervisor's supervisor's supervisor--you get the point--each person telling the new person about my case in Hindi, not allowing me to tell it myself, and each new person telling me I needed to go back to Jaipur to get my registration papers. Finally, as we got to the highest ranking supervisor's office, I got tired of having people speak about me for me. I jammed my trolley full of luggage in his doorway, ran inside, and started talking as fast as I could (but also as politely as possible), determined to get my story out before someone told their version of it. First thing this newest supervisor did was ask me to please get my trolley out of the doorway. Politely, I removed my 100 pounds of luggage from his doorway, stepped back in, and continued my story, which thank goodness, he listened to. At the end of my spiel, he told me, sorry, I needed to go back to Jaipur to get the papers. At that point, I decided the pity tears that would not take very long to conjure maybe would do me some good. So, I started the waterworks, telling him how my visa expired in a few days, which thankfully had its desired effect. Telling me to "please sit and calm down, ma'am," the supervisor of the supervisor of the supervisor went to call his supervisor. When he came back into the office, he said that though I would not be able to get on a plane tonight, he had good news--that I could go to the Mumbai FRO and register from there the next day and hopefully fly the next night. Having learned my lesson about government officers who make assurances without giving me appropriate paperwork with their signatures (the golden ticket for anyone wishing to get anything done--a paper stamped, signed, and stuck with photographs is key), I asked Mr. Supervisor^3 if I could have a piece of paper from him saying that I could register at the Mumbai FRO and that the registration needed to be completed in a day. Waving his hand, he told me his supervisor had already called and it would all be fine--I just needed to walk in the next day and get my paperwork processed.

As my uncle's driver picked me up from the airport around midnight for the second time, I called the number the nice Continental man had given me to explain my situation and postpone my flight. Knowing that this registration could well take a few days, I wanted to reschedule for a couple days later. However, the lady told me some bleak news: there was only 1 flight going out in the next few days, and it was going out tomorrow, on June 7. There were no flights on June 8 and 9, and on June 10, my visa was due to expire.

I was definitely going to HAVE to get my registration processed tomorrow if I wanted to leave the country anytime soon.

I was dropped off at the Mumbai airport 9pm with all of my luggage for the second night in a row (my dad had accidentally switched my flights the night before, so though the driver had dropped me off, when I got to the check-in desk, I found that my itinerary was for the next day). Of course, when I got to the front of the check-in line, one bag weighed too much and I hurriedly started stuffing things from one bag into another. Finally getting both bags to their correct weight limit, I again went through the line, when a Continental staff member examined my passport and asked to see my registration. "What registration? The Jaipur Foreign Registration Office (FRO) said I didn't need to register since my visa was under 6 months..." The nice Continental guy told me he would put my luggage on hold until Immigration cleared me. That's when my panic started. I had just read all about how Indian Immigration had gotten very strict with American citizens in allowing them to enter and re-enter the country; however, I didn't know they would also stop me from LEAVING! Having had many experiences in getting through bureaucracy to get where I needed when I helped take slum children to the municipal (government) hospital with Manav Sadhna, I put on my polite-but-won't-back-down face and went back to immigration.

As predicted, when I got to the immigration officer, he took one look at my student visa and asked for my registration. I repeated what I had said before--that my study abroad program had taken our whole student group to register at the Jaipur FRO, but they told some of us that we did not need to register and sent us back--and all of the other students in my program were allowed to go back to the US. What could I do if the FRO officer didn't give me registration papers? Of course there is no computer system that records these kinds of things--people who have gone to the FRO and registered, people that haven't, people that have gone and were not given registration--why use technology to lessen paperwork? No, just like medical records and tax records, these sorts of things are all recorded on papers that have to be stamped, signed, and photographed multiple times--papers that we all have to carry around if we have any hope of getting anything done.

[Pictures of the AUDA tax office in Usmapura in Ahmedabad.The room goes on for awhile, and all of the shelves, tables, and most of the floorspace is occupied by dusty files containing tax information. One lone desktop computer sits in the corner of the room--located on the left side of the top picture--and only those lucky enough to have a key number have their business taken care of by using a computerized system. For everyone else, tax officers sit and sort through thousands of names in files which are organized by some archaic system that is not alphabetical and which I have a real suspicion that even the government workers in the office do not know how to search through...we almost went through that process when we were there, but luckily, Ajaybhai called and found a number and we were able to look up the file on the COMPUTER!]

{also, the pictures of Hindu gods in a government office may seem surprising for a democracy, but that has to do with India's definition of secularism, which is quite different from the western definition...but I'll leave that discussion for later!}

I was sent back out to look through my packed luggage to see if my registration papers were hidden somewhere. So, I frantically began searching through my check-in baggage in the middle of the airport, stacking all of the papers I had stuffed in my bag (I am supposed to lug home all of the materials I used in my study abroad classes to make sure I get appropriate credit from my university) all around me as the nice Continental guy stood looking down at me sympathetically. I called my professors in Jaipur telling them what was going on, and they confirmed my fears--I could not find my registration papers because the Jaipur FRO did not give me any. As the nice Continental guy started ripping my check-in tags off my baggage, I held back tears, determined not to look more pitiful than I already did--in the middle of the airport pulling up my jeans that were now a million sizes too big because of all the weight I had lost, disheveled hair in a ponytail that was loosening itself by the minute, with about 10 pounds of paper now strewn across the floor. Gathering everything onto a trolley, I went back to the immigration officer to see if I could talk my way onto the plane.

Of course, I wasn't allowed. He walked me and all of the luggage I was heaving around back to the offices of his supervisor and his supervisor's supervisor and his supervisor's supervisor's supervisor--you get the point--each person telling the new person about my case in Hindi, not allowing me to tell it myself, and each new person telling me I needed to go back to Jaipur to get my registration papers. Finally, as we got to the highest ranking supervisor's office, I got tired of having people speak about me for me. I jammed my trolley full of luggage in his doorway, ran inside, and started talking as fast as I could (but also as politely as possible), determined to get my story out before someone told their version of it. First thing this newest supervisor did was ask me to please get my trolley out of the doorway. Politely, I removed my 100 pounds of luggage from his doorway, stepped back in, and continued my story, which thank goodness, he listened to. At the end of my spiel, he told me, sorry, I needed to go back to Jaipur to get the papers. At that point, I decided the pity tears that would not take very long to conjure maybe would do me some good. So, I started the waterworks, telling him how my visa expired in a few days, which thankfully had its desired effect. Telling me to "please sit and calm down, ma'am," the supervisor of the supervisor of the supervisor went to call his supervisor. When he came back into the office, he said that though I would not be able to get on a plane tonight, he had good news--that I could go to the Mumbai FRO and register from there the next day and hopefully fly the next night. Having learned my lesson about government officers who make assurances without giving me appropriate paperwork with their signatures (the golden ticket for anyone wishing to get anything done--a paper stamped, signed, and stuck with photographs is key), I asked Mr. Supervisor^3 if I could have a piece of paper from him saying that I could register at the Mumbai FRO and that the registration needed to be completed in a day. Waving his hand, he told me his supervisor had already called and it would all be fine--I just needed to walk in the next day and get my paperwork processed.

As my uncle's driver picked me up from the airport around midnight for the second time, I called the number the nice Continental man had given me to explain my situation and postpone my flight. Knowing that this registration could well take a few days, I wanted to reschedule for a couple days later. However, the lady told me some bleak news: there was only 1 flight going out in the next few days, and it was going out tomorrow, on June 7. There were no flights on June 8 and 9, and on June 10, my visa was due to expire.

I was definitely going to HAVE to get my registration processed tomorrow if I wanted to leave the country anytime soon.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)